- Like

- SHARE

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Flattr

- Buffer

- Love This

- Save

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- JOIN

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

Recognizing Hypermobility and Joint Hypermobility Syndrome

Recognizing Hypermobility and Joint Hypermobility Syndrome

When you come across a client that exhibits hypermobile joints, do you dismiss it as something of no real importance, or do you take note and assess further?

What is it?

Hypermobility is a condition in which the joints easily move beyond the normal range expected for a particular joint. Hypermobility should probably now be added to the medical screening form your clients complete as part of their initial assessment or, at least pertinent questions asked, if you see evidence of hypermobility in your clients’ posture or movement.

Hypermobility is a condition in which the joints easily move beyond the normal range expected for a particular joint. Hypermobility should probably now be added to the medical screening form your clients complete as part of their initial assessment or, at least pertinent questions asked, if you see evidence of hypermobility in your clients’ posture or movement.

Joint hypermobility occurs when proteins within the connective tissue of structures like bone, cartilage, tendons and ligaments, muscle and skin are differently formed, resulting in these structures being laxer, more mobile and/or more fragile than normal. The shape of bony articulating surfaces (i.e. joints being shallow), neuromuscular tone and reduced proprioception can also contribute to the condition. The joints affected will have larger than normal range of movement.

Hypermobility of itself may not present a problem or need treatment. However, it might still influence the content of the programme you devise for your client. You may want to ensure the inclusion of strength and stability exercises that address particular joint laxity. You might also wish to exclude flexibility exercises for the joint(s) concerned because of the existing, excessive range of movement. Your assessment may highlight that flexibility exercises need to be included for other joints and muscles that have become stiff or less mobile because they have taken on a protective, stabilising role to counteract the excess movement available at the hypermobile joint(s).

It is also important, as a personal trainer or instructor, you are aware that in some cases, people who have joint hypermobility also suffer chronic, non-inflammatory joint and back pain (arthralgia – which literally means joint pain), soft tissue injuries (which can be sporting injuries or conditions like tenosynovitis), a higher incidence of joint dislocations and/or fatigue. This condition is known as Joint Hypermobility Syndrome (JHS); formerly Benign Joint Hypermobility Syndrome (BJHS). In its most complex form, JHS may also include autonomic dysfunction resulting in dizziness or fainting, proprioceptive impairment, premature osteoarthritis, intestinal issues like sluggish bowels and bloating, and laxity in other tissues resulting in hernias, uterine or rectal prolapse or varicose veins. The chronic pain or fear of pain can lead to decreased mobility, disability, and impaired quality of life.

Prevalence

Formal prevalence figures state JHS occurs in 10-20% of western populations; having an even higher prevalence in Middle Eastern, Indian and Chinese populations (BMJ 2011). However, because of poor diagnosis the actual incidence is thought to be much higher. This is attributed to doctors being unaware of the prevalence of the condition and so not routinely considering this as a possibility when patients present with what they consider to be common, everyday, non-inflammatory, painful, musculoskeletal conditions.

The condition is more common in females and scoliosis is thought to occur more commonly in sufferers.

Diagnosis

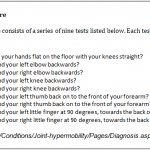

The initial Beighton 9 point scoring system (Box 1), devised in 1973 to identify hypermobility, has now been incorporated into the Brighton criteria (1998) (Box 2). The latter has proved more sensitive and more accurate in diagnosing JHS.

There is discussion in the medical community as to whether Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndromes (that have similar symptoms) are the same as JHS. This is does not really affect your role in dealing with sufferers of any of these conditions, as the management is the same.

If you are concerned about a client that presents with some of these symptoms and suspect that they may have JHS, you should refer them on to their GP, a physiotherapist or other specialist. Clearly state why you are making the referral and give as much detail as possible relative to what you have seen and found.

Why is it important?

As sufferers are often not diagnosed for years, you could be the person who makes the link and needs to make a referral on to their GP or other clinical practitioner. It may be the client has dismissed symptoms as general aches and pains and not seen a clinical practitioner. It is also good to have a full picture of your client’s health issues and an understanding of how this might affect what you do with them and how you can assist their management of their condition through advice and appropriate programming.

Exercise can help:

- reduce pain

- improve muscle strength and fitness

- improve posture

- improve body awareness

- correct the movement at individual joints

- address tightness and stiffness at other joints

- increase confidence and address psychological aspects

As a personal trainer/instructor, you would likely focus on:

- Core and joint stabilizing and proprioception enhancing exercises

- Specific muscular strength exercises for the muscles surrounding the affected joints

- General fitness training to offset or reverse decreased activity levels due to pain or fear of pain

- Postural education and awareness training

- The use of mobilizing and stretching techniques to restore normal mobility to joints or spinal segments that have become stiff or less mobile as a result of deconditioning or self protection

- Designing a home exercise or supporting exercise/physical activity programme and providing appropriate education

The clients in the following case studies both presented knowing they were hypermobile and suffering from JHS. It is not to say that you would do anything differently for these two clients than you would for anyone else presenting with similar issues but the exercise programme must be appropriate and designed relative to the needs of the individual. This is because of the possibly of higher risks of subluxation or dislocation of intervertebral or peripheral joints; rupture of ligaments, joint capsules, muscles, or tendons, or pathological fractures where bone changes may have resulted in osteoporosis. Hence, screening for JHS or symptoms associated with the condition can help you be in a more informed position to effectively service your clients.

Case Study 1

The client presented with severe lower back pain that had worsened over the previous 2 months. The pain was getting her down and making her distressed. She admitted she has spent her life avoiding pain by restricting what she does and doing minimal activity. This has resulted in poor muscle strength, poor bone density and increasing stiffness in particular joints as she reaches menopausal age whilst remaining hypermobile in others.

She was given a light mobility programme to do daily. This included some core strengthening exercises and basic strength exercises for her gluteals (as these were weak and likely contributing to the incidence of low back pain). Postural awareness advice was also given.

The client reported improvement in her back pain within 2 weeks. This lifted her mood and reduced her distress.

Case Study 2

The client presented with upper back and neck pain. He has always been very active as an actor and would often be cast in roles requiring or demanding extreme positions, because he could do them. Doing them on a regular basis helped his fitness and muscular strength. However, now that he is taking a break from acting and those sorts of roles, he is finding that he is in constant pain.

An assessment of his movement confirmed that although hypermobile in some thoracic joints he was very stiff in his lumbar spine. This resulting imbalance, in some muscles being excessively tight while others were lengthened, seemed to exacerbate the stiffness and pain.

Gentle joint manipulations (done by a physiotherapist) helped loosen the stiff joints and soft tissue massage (which could be part of your role if you are qualified in massage), helped to release muscle tension around the joints. This helped lessen the upper back pain. This was complimented by stretching exercises for tight muscles, strength exercises for weak muscles and postural advice relating to upper body positioning.

The client reported improved back pain. Although he felt slightly more discomfort in his neck initially, he reflected this was due to him being more aware of the neck pain now that the back pain was less. The neck pain was then more specifically addressed in a similar way.

References:

1. Juliette Ross, Rodney Grahame, Joint hypermobility syndrome BMJ 2011;342:c7167 http://www.bmj.com/content/342/bmj.c7167?keytype=ref&siteid=bmjjournals&ijkey=Lw4LnyH/eWJwA

2. Grahame R, Bird HA, Child A et al. The revised (Brighton 1998) criteria for the diagnosis of benign joint hypermobility syndrome (BJHS). J Rheumatol 2000 Jul;27(7):1777-9

About Michael Betts

Fitness Industry Education Michael Betts is a Director at Fitness Industry Education in the UK. He is a recognised expert in all aspects of personal training and fitness. Michael is dedicated to sharing information and knowledge to help continually improve the industry.